Link to Article on The Red & Black

Olivia Sayer

(Photo Courtesy/Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

G.A.T.A. — “get after them aggressively” or what is more commonly known to fans as “get after their a**.”

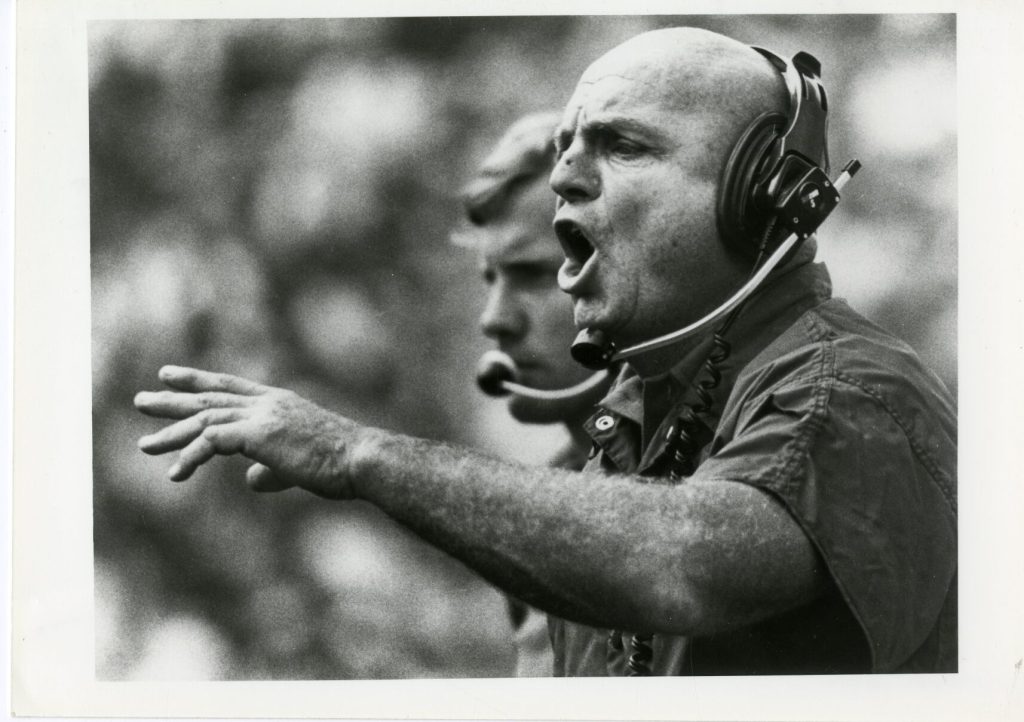

Former Georgia defensive coordinator Erk Russell embodied the message better than most, often tackling and headbutting players during pregame warmups. His 1980 defense — nicknamed the ‘Junkyard Dawgs’ — was known for its physicality and toughness.

Georgia’s 2024 defense resembled the ‘Junkyard Dawgs’ on Saturday in the SEC championship. With six sacks and 15 tackles for a loss, the Bulldogs aggressively got after Texas in their 22-19 overtime victory. Georgia will now play the winner of Indiana-Notre Dame in the Sugar Bowl, at the same stadium Russell’s Junkyard Dawgs held the Fighting Irish to 10 points in to win the 1980 national championship.

It’s no surprise that Russell was the author of G.A.T.A. He created the acronym as a play on Georgia Tech’s G.T.A.A. (Georgia Tech Athletic Association) that he saw on the back of every chair next to the visiting locker room at Grant Field.

Throughout Georgia’s 2024 season, the acronym G.A.T.A. was plastered in its usual position near the southwest tunnel of Sanford Stadium. The sign embodies the passion Russell brought to the Bulldogs but also serves as a constant reminder of the one accolade missing from his prestigious career.

A sign reading “G.A.T.A” sits in the southwest corner of Sanford Stadium. Former defensive coordinator Erk Russell created the acronym as a play on Georgia Tech’s “G.T.A.A” acronym. (Photo/Olivia Sayer)

Despite winning four national championships — including three as the head coach at Georgia Southern — Russell is ineligible for the College Football Hall of Fame due to a technicality. He only coached the Eagles for eight years, which is two years short of the minimum requirement.

Russell surpassed all other criteria, however, with a .788 winning percentage (minimum is .600) in 106 games coached (minimum is 100). He retired in 1989 as America’s winningest football coach at the time.

Hillary Jeffries, the director of special projects at The National Football Foundation, said Russell has “been on our radar for a long time.” However, his accomplishments “fall slightly short” of the Hall of Fame’s criteria.

Jeffries was not with The National Football Foundation when it set the requirements, but she believes its resistance against exemptions is due to the committee wanting to recognize coaches who had consistent success.

“This is still something that we want to abide by,” Jeffries told The Red & Black. “The selection committee feels that it is our due diligence to recognize those who have been a head coach over a long period of time and to have had a great winning percentage and maintain that over a long period of time.”

Although Russell lacks the required qualifications to enter the College Football Hall of Fame, his story lives on through the many lives he touched. The Red & Black reached out to Russell’s former colleagues, players and others in the industry to highlight his legacy and share why he should have a spot in the prestigious hall.

“He’s in there on a brick.”

Although Russell himself is not in the College Football Hall of Fame, his name is a part of its foundation. During the building’s construction, the Hall of Fame ran a promotion that allowed customers to buy and engrave a brick to help build the 94,256 square foot structure.

As a part of its partnership with local radio station 680 The Fan, the Hall of Fame gave talk show host and former Georgia quarterback Buck Belue a brick to “engrave what he wants” on it. Belue, who said Russell “should be in the Hall of Fame,” decided to etch the name of his former defensive coordinator.

“I put ‘Erk Russell, defensive coordinator of the ‘Junkyard Dawgs’ on the brick,’” Belue said. “So we could get Erk in the College Football Hall of Fame.”

Belue’s favorite memory with Russell occurred after the 1980 Georgia-Florida game, when Lindsay Scott infamously took a crossing route 93 yards to the end zone. Belue said that Russell always carried a big cigar in the pocket of his blazer when the team traveled. After the Bulldogs beat the Gators 26-21, Russell gifted the cigar to his quarterback.

“He came up to me and put that cigar in my sport coat pocket and said, ‘You know you deserve it, kid. Great, great, going out there. Why don’t you smoke this cigar for me this time,’” Belue said. “Of course, I never did smoke it. I just kept it. That was special.”

“He was what a good parent should be.”

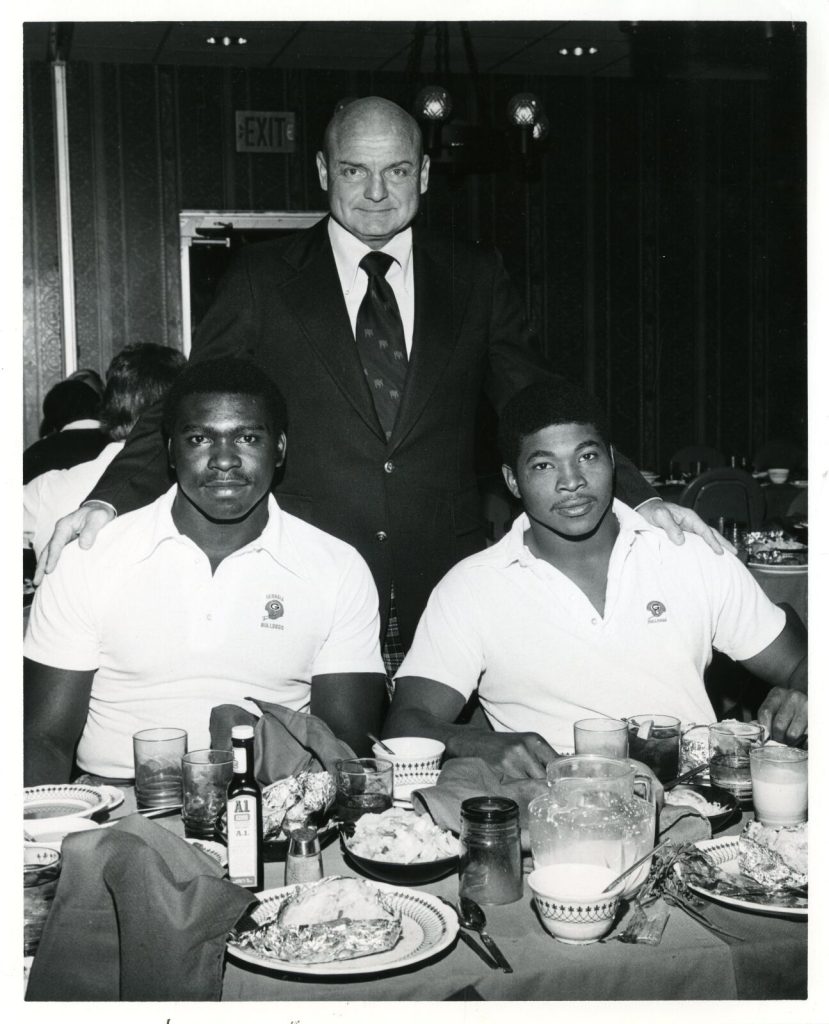

Those around Russell clearly respected him. However, it was not due to fear, but rather because Russell made it known to his players that he cared for them.

“He was what I say a good parent should be,” said Chris Welton, a member of Georgia’s ‘Junkyard Dawgs’ defense. “If you felt like Coach Russell was pleased with your effort and the job you were doing, it was kind of like everything was right with the world. And that’s why he was able to motivate people so well, was because people just didn’t want to let him down.”

Russell’s treatment of others is why countless former players and colleagues are dedicated to defending him. Frank Ros, captain of Georgia’s 1980 defense, reached out to his teammates from the 1980 team and requested they write letters to executive director Steve Hatchell in support of Russell earning a place in the Hall of Fame.

“Write it from your heart like he touched all of ours,” Ros wrote in the message to his teammates.

Welton was one of Ros’ teammates to send in a letter, but he said it was “like a voice crying in the wilderness.”

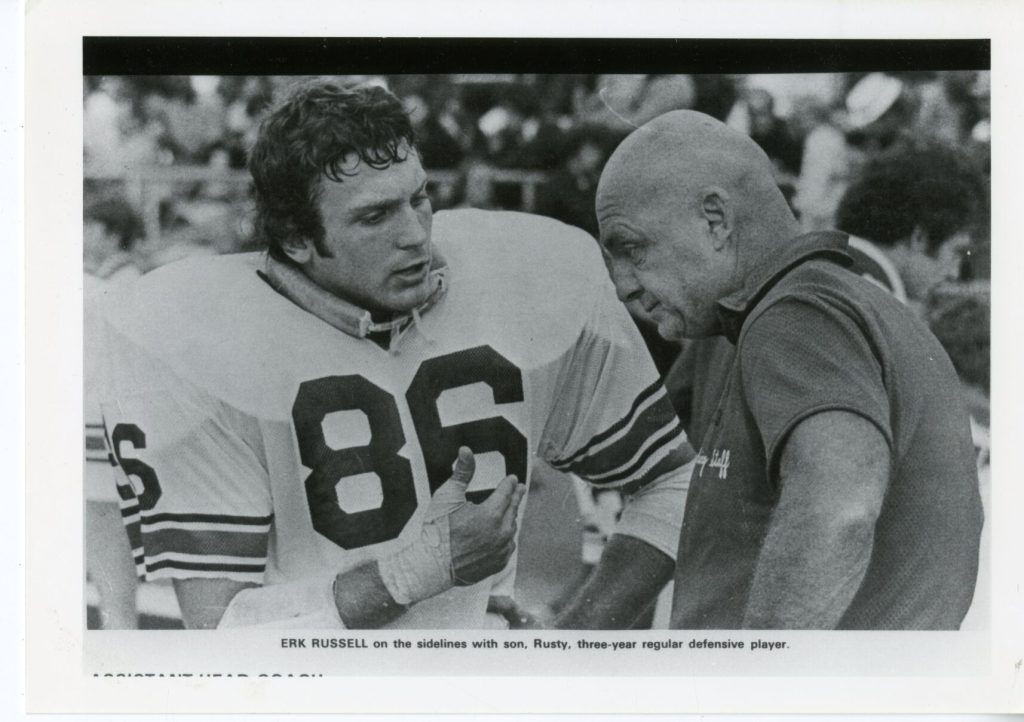

Erk Russell stands on the sideline with son Rusty Russell. (Photo Courtesy/Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Georgia Southern tried a similar tactic in 2022, as athletic director and Georgia alumnus Jared Benko sent a letter to Hatchell, urging the committee to issue a waiver on-behalf of Russell. Benko said the response was “silent” on why the committee was not willing to change its stance.

“You’d be hard pressed to find anybody in the state of Georgia, between [Georgia Southern and Georgia’s] fan bases that would not climb the highest mountain and yell at the top of their voice that he needs to be in the Hall of Fame,” said Benko, who accepted a job with Auburn in October.

“He was a master motivator.”

Russell had a unique way of motivating his players. He rarely used profanity towards them, according to Georgia historian Loran Smith, but excelled with communicating and relating to people — even if they wore opposing colors.

One example occurred in Knoxville, Tennessee, when Russell spoke at the request of Phillip Fulmer. He delivered a line that all-but won over Volunteer fans.

“He said, ‘When my time is over and my time has come to pass, I want you to bury me upside down so the Florida Gators can kiss that…,’” Smith said. “His ability to communicate with humor was so poignant, so sensitive, and he also could relate to all ages.”

Fulmer described Russell as “an icon,” saying he “was the guy that everybody looked up to.” He also said the Hall of Fame — which Fulmer worked for as a part of its oversight committee — is in a “difficult spot” with Russell’s exclusion.

“Unfortunately there’s coaches out there that land a little bit under something or another,” Fulmer said. “And somewhere, you gotta draw the line I guess.”

Benko said if anyone deserves an exemption, it is Russell.

“I respect that there’s always rules and regulations to most things in life,” said Benko, who described latching on to a set criteria as “myopic.” “But in the same standpoint, there’s always exceptions to the rule.”

(Photo Courtesy/Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Russell often provided hands-on motivation, such as his intense pregame warmups that involved headbutting players with blood running off his nose and down his face. The routine had a young Belue, who witnessed the routine when attending Georgia games with his family, initially believing Russell was “the meanest man on Earth.” The image left a lasting impression, but Belue quickly realized upon arriving at Georgia that his perception was inaccurate.

“There was nothing mean about him,” Belue said. “He was the master motivator, and he did it — not through yelling and hollering at people — he did it by encouraging the players.”

Ros agreed and said he would “run through a wall” for his former defensive coordinator due to his constant encouragement over beratement.

“A lot of coaches will just start ripping you and usually attack you, not your action,” Ros said. “Coach Russell had an ability to calmly address you [and] address the action that you took that you made a mistake on. Not criticize you, but correct you.”

“He had a way of getting his point home.”

Russell had unexpected ways of captivating his audience, with no idea too crazy for him to try. After Maryland basketball star Len Bias died from cardiac arrhythmia induced by a cocaine overdose in 1986, Russell knew he wanted to emphasize the danger of drugs to his Georgia Southern team.

The presentation began on a humorous note, as Russell mimicked the mannerisms resembling someone taking the drugs displayed on a table in front of him. With laughter echoing throughout the team meeting room, Russell threw a rattlesnake on the table. The mood shifted abruptly, with players and coaches bolting for the exits.

“They made doors where there wasn’t any,” said Paul Johnson, who was an assistant on Russell’s staff at the time.

The rattlesnake method may have been unconventional, but it got the point across, according to the longtime Georgia Tech head coach.

“He said, ‘Hey, get your butt back in here. You’re sitting here and laugh and cut up, and we had all these drugs in here. And then when the snake comes, you run,’” Johnson said. “He said that snake hadn’t killed anybody, and those drugs have destroyed all kinds of people.”

Johnson, who was a 2023 College Football Hall of fame inductee, said it is “disappointing” that Russell is not alongside him.

“He meets every qualification except that one, and he was a big part of college football,” Johnson said. “But I also understand they have rules. So it’s just disappointing. He would certainly be in the College Football Hall of Fame if he had two more years as a head coach.”

“He changed the landscape of the whole school.”

One could argue that Russell did not coach the required 10 years because he did not need to. It only took him eight to win three national championships with a Georgia Southern program that did not field a football team in the 20 years prior to his arrival.

He began in 1981 with nothing — including helmets, which he purchased from high schools and other colleges — and retired after a 15-0 season in 1989 with 19 Coach of the Year awards and a rebuilt football program.

“He should be in the Hall of Fame,” said Welton, whose emotion was evident, even through the phone. “I know he didn’t have the 10 years as a head coach, but he left because he thought he had done all he could do and built that program from scratch into something that was great.”

Georgia Southern recognized Russell with a bronze statue in 2012 and named a part of its campus the “Erk Russell Athletic Park” a year later. He is honored in the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame, the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame and the Georgia Southern Athletics Hall of Fame. Now, those in the industry are awaiting for the College Football Hall of Fame to call Russell’s name.

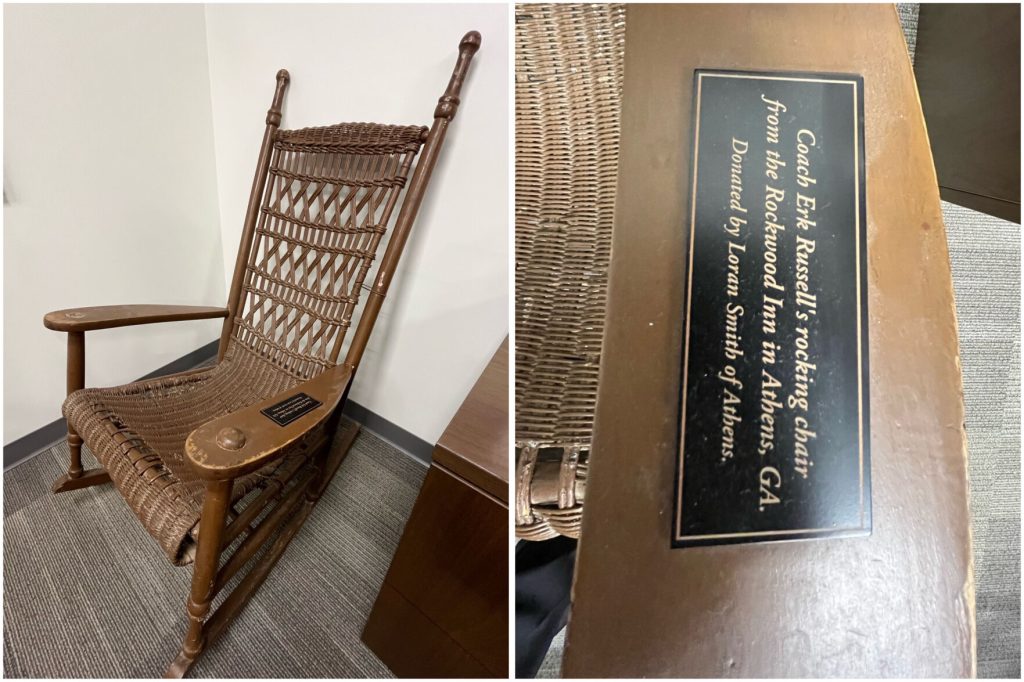

“Disappointment, frustration, astonishment that he’s not recognized in the Hall of Fame,” said Benko, who has Russell’s old chair from the Athens Rockwood Inn in his office. “There’s some things that are just really arbitrary that I would say take away from the spirit of what the Hall of Fame is supposed to represent.”

Erk Russell’s rocking chair from the Rockwood Inn now sits in the office of former Georgia Southern athletic director Jared Benko. Benko received the chair from Loran Smith, who said that people frequently spoke to Russell at the Rockwood Inn, and he “just let them talk, made them feel good [and] made them feel like they were [adequate].” (Photos Courtesy/Bryan Johnston)

Benko said that Russell transformed Georgia Southern’s community and school. He credits him for the university now hosting over 27,000 students, a 5.4% increase from Fall 2023.

Russell also started many of Georgia Southern’s rally cries, such as the mystical water in Beautiful Eagle Creek. The tradition began when he told a manager to go to the creek, fill up an empty milk jug with its water and bring it on the team’s next road trip.

Before the game, Russell called all the players over to the end zone and began pouring the creek water on the field. According to Benko, it was Russell’s way of combating the Eagles playing in “foreign territory.” Apparently it was also just one of many random rally cries Russell created.

“I would see that creek [and wouldn’t think twice about it],” Ros said. “He sees a creek, and all of a sudden, this is a rallying point…He had an uncanny ability to do that.”

“He’s doing something no one can stop.”

Russell’s 1980 Georgia defense surrendered an average of just 11.4 points per game, but it was his wishbone offense at Georgia Southern that stood out to his colleagues. He ran the triple option, which according to three-time national champion and Super Bowl winner Barry Switzer, was “something no one can stop.”

“Have you ever seen anybody with a ball run at someone, and the defender run away from him — not coming to tackle him?” Switzer said. “I’ve got the ball under my arm, and the guy in front of me is on defense. And he’s running away from me instead of coming to get me. That’s what the wishbone does to you.”

Russell’s offense made defenders think, while limiting their ability to play aggressively. Having multiple options — such as a quarterback keeper or pitch out to the perimeter — essentially took a defender out of the play and left defenses vulnerable to play-action.

“It makes defenses react different ways than they’ve ever had to react,” Switzer said. “They’re doing something that in the 10 games they play, this is one game that it’s different, and they have to play it differently.”

Switzer, who also ran the wishbone with Oklahoma, said that Russell’s offensive scheme would still work in today’s game. He believes the wishbone offense would “wear teams out,” especially those who “try to throw the damn ball over the field,” rather than “playing against what [the opposing offense] is doing.”

Switzer’s Oklahoma teams never faced Russell’s Georgia Southern ones, but the 2001 College Football Hall of Fame inductee watched enough film to know that Russell’s teams “kicked everyone’s a**.” Switzer was also surprised to learn Russell was not in the Hall of Fame and said his accomplishments were “definitely good enough to be in there.”

“He loved Georgia.”

Russell’s passion for Georgia was evident to those around him. Belue said he frequently saw his defensive coordinator at other Georgia sporting events, while Fulmer mentioned that Russell was a coach he would eagerly play for.

“He just had such great energy and passion for the position, for the young men that played with him,” said Fulmer, who played against Russell’s defense as a member of Tennessee’s offensive line. “He loved Georgia, loved being there.”

Russell almost had an opportunity to lead the team he loved so much after Auburn offered Vince Dooley its head coaching job prior to Georgia’s 1981 Sugar Bowl game against Notre Dame. Dooley ended up staying with the Bulldogs, but the team’s trust in Russell left them unfazed during the rumors.

“We were all stunned and shocked that first day,” Belue said. “And then that second day, the word started getting around that have no fear, Erk’s going to step in and take over. So it was just a feeling of relief.”

Russell’s love for the Bulldogs did not end with his coaching career, as Mark Richt invited him to speak with the team. When asked what stood out from stories shared about Russell, Richt said “his passion for Georgia and his hate for Georgia Tech.”

“I don’t think he ever called them Georgia Tech. I think he called them North Avenue trade school or something like that,” Richt said. “He had some kind of name for him, he would never say their name.”

(Photo Courtesy/Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

“His mission in life was to touch people.”

Although Russell often appeared fired up on the sidelines, away from the field, Benko described him as a “big teddy bear” and a “person of Faith.”

His son Jay Russell said putting Erk in the College Football Hall of Fame would be an “appropriate gesture” and one that he “certainly earned.” However, his dad was not motivated by material accolades. Instead, Russell judged success by the number of lives he positively impacted.

“I can tell you that if he were here, that wouldn’t really matter,” Jay Russell said about the push to get Erk into the College Football Hall of Fame. “He wouldn’t be fighting for it. He wouldn’t be lobbying for it because he measures success by the lives that we touched.”

That does not mean those who crossed paths with Russell will stop fighting for his recognition, and one Georgia Lettermen believes the university is in the perfect place to lead the charge.

“Georgia has as much prestige and influence as any [university],” Welton said. “I’d like to see [Georgia Southern] take a little stronger position and maybe redo the effort to try to get him in, but this time led by the University of Georgia.”

The Red & Black reached out to CEO of the Hall of Fame Kimberly Beaudin, but she was unable to comment because she is “removed from the selection process.”